La Alianza Domestic Worker Surveys - 2025 Year-End Report

“WE KEEP FIGHTING, BUT THESE ARE TERRIBLE TIMES”

Deteriorating conditions for Spanish-speaking domestic workers in 2025

January 2026

The year 2025 was marked by unbridled attacks on immigrants, people of color, workers, and working-class families. The nation’s >2 million domestic workers—and, by extension, the people they care for—are particularly vulnerable to these attacks. These nannies, house cleaners, and home care workers are disproportionately Hispanic, Black, and Asian immigrant women. They make essential contributions to the US economy, yet are paid far less than the average worker and are three times as likely to be living in poverty, often relying on several jobs across multiple employers and still struggling to make ends meet.

The National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) has been surveying Spanish-speaking domestic workers since March 2020 to track employment conditions and economic trends over time. This report analyzes survey data alongside worker testimonies to understand how and why conditions for domestic workers changed leading up to and during 2025.

Summary

Following the COVID-19 pandemic’s devastating impact on the domestic workforce, employment conditions recovered slowly and tenuously from 2020 to 2024, while difficulties affording housing, food, and other basic needs initially eased before resurging by the end of 2024.

Employment and economic conditions worsened in 2025, marked by a sharp decline in Q3 (including record-high economic insecurity) and crisis levels that persisted in Q4.

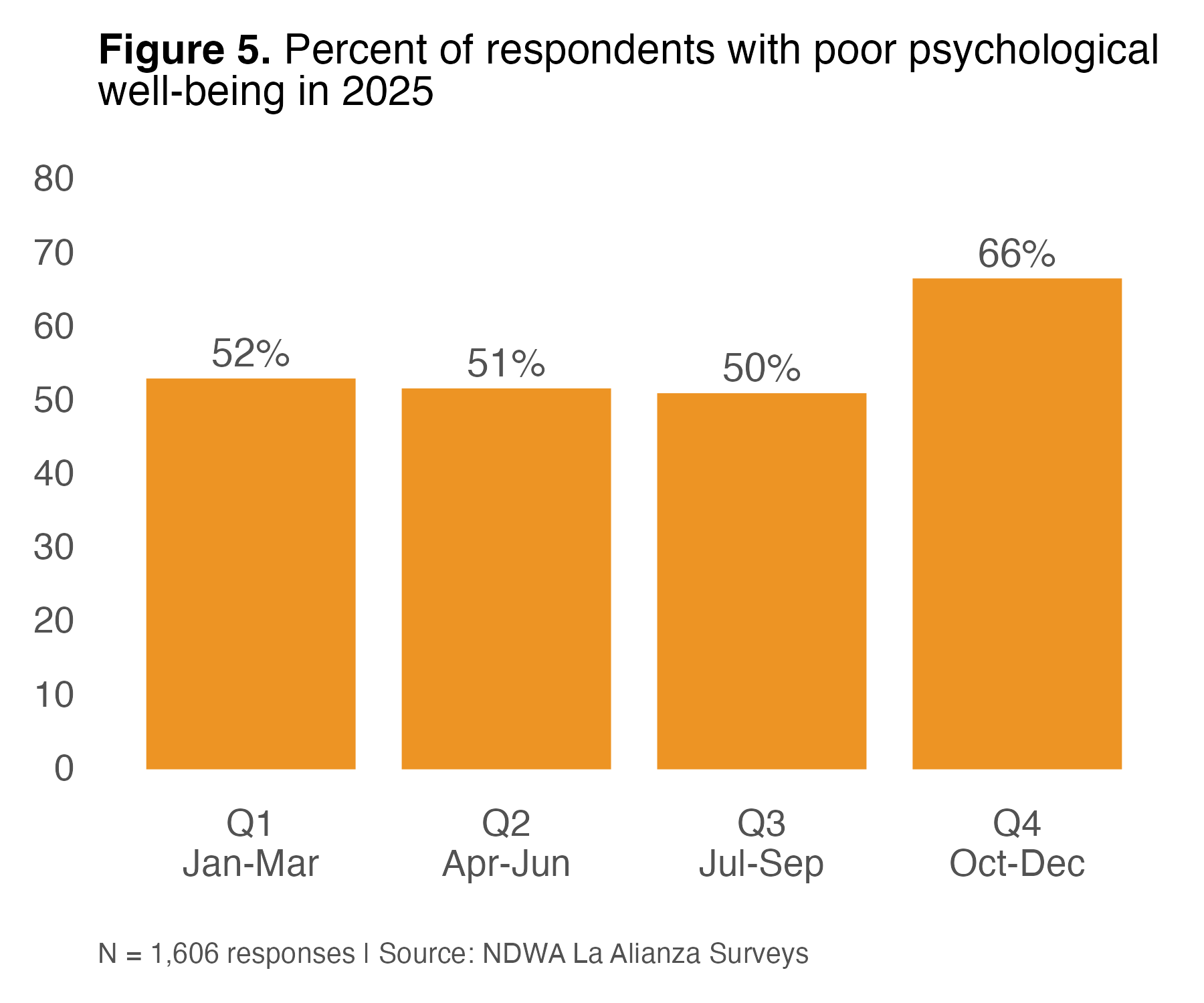

As workers increasingly struggled to find work and make ends meet, poor mental health spiked from an already alarming ~50% in Q1-Q3 2025 to 66% in Q4.

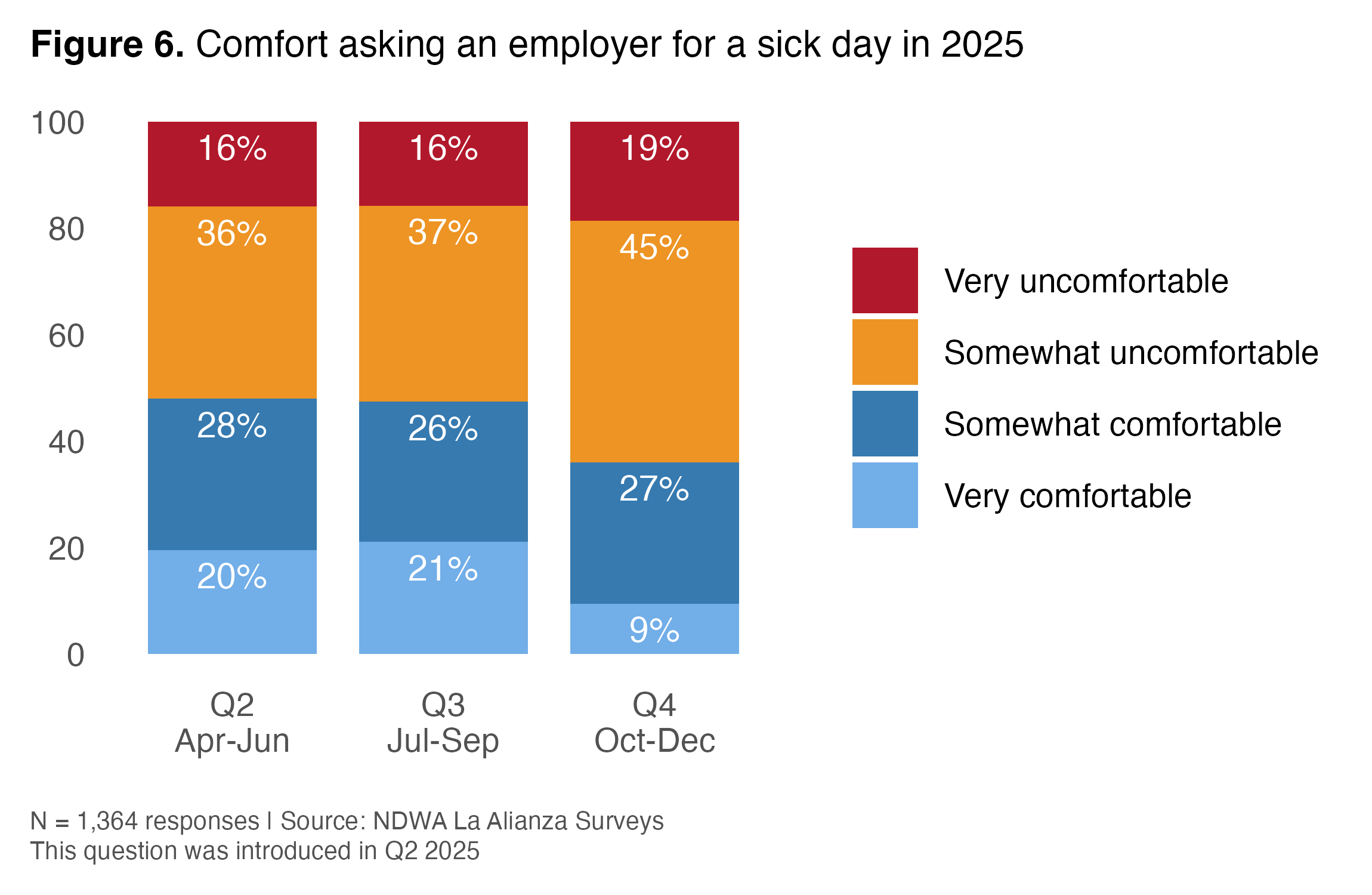

Measures of employer-worker power dynamics also deteriorated with, for example, 20-21% of workers feeling very comfortable asking for a sick day in Q2-Q3 2025 versus just 9% in Q4.

Worker testimonies gathered through other NDWA channels—paired with supporting survey data—highlighted widespread immigration-related fears and economic uncertainty in Spring 2025, escalating to acute economic strain, mental health burdens, and domestic labor market disruptions by Fall.

Data overview

This report features the 10,929 complete responses from 5,217 Spanish-speaking domestic workers to one or more of the 24 biweekly surveys conducted via La Alianza during 2025. This report also includes survey data from 2020 to 2024 and testimonies from nannies, home care workers, and house cleaners collected during Spring-Fall 2025 as part of a NDWA Worker Council Peer Research Project.

Employment and economic conditions from 2020-2024

La Alianza survey data collected since March 2020 indicated a slow and non-linear recovery from the widespread, devastating disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

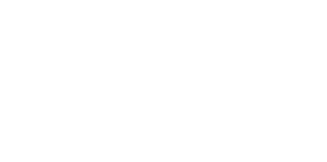

Slow post-pandemic recovery in employment conditions. The percent of domestic worker respondents who worked zero hours in the last 7 days was 41% in Q4 2020, fell to 23% by Q4 2021, and saw more marginal progress from then on (Q4 2022: 20%, Q4 2023: 18%, Q4 2024: 17%) (Figure 1).

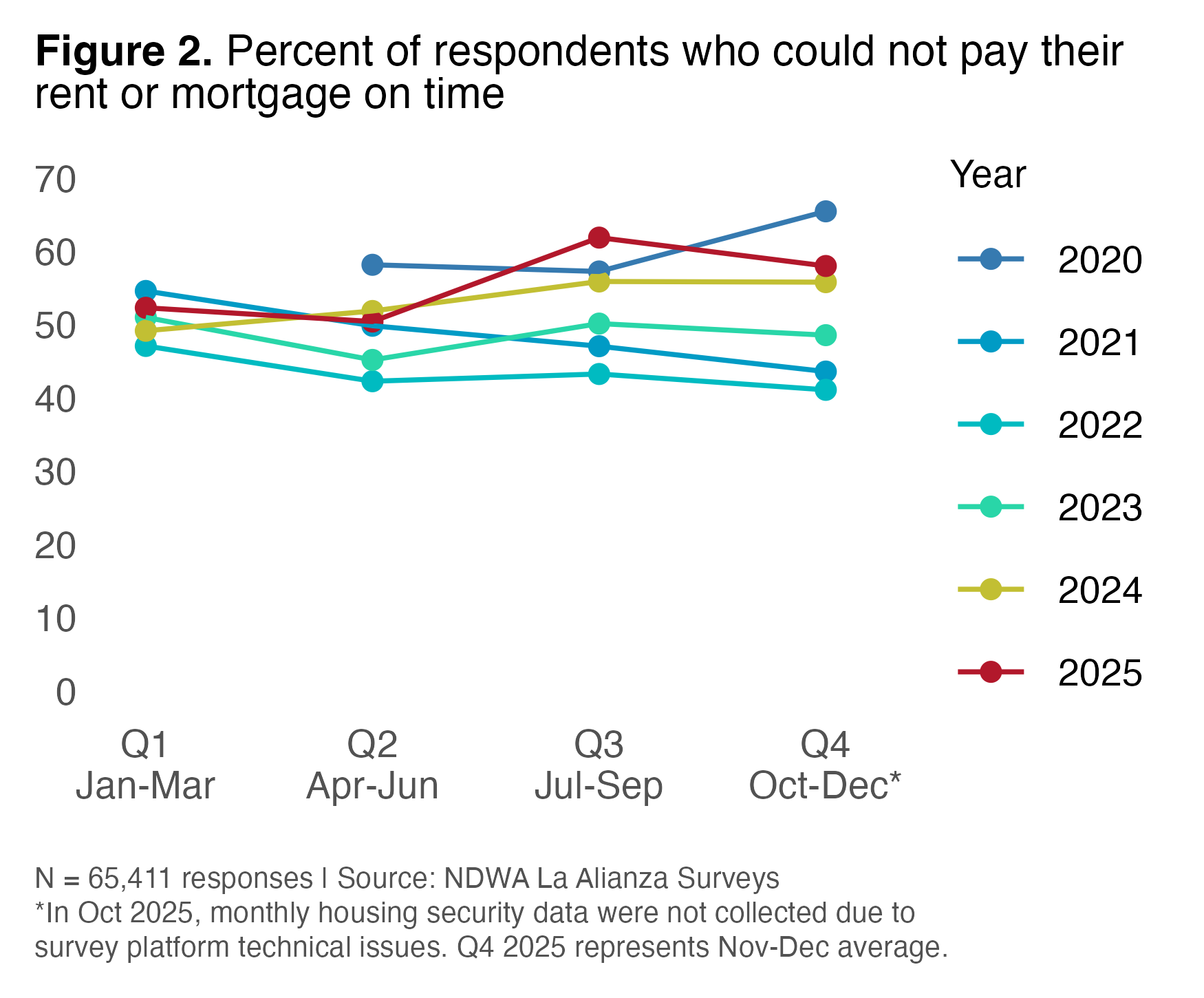

Among respondents who were still working more than zero hours, 92% wanted more hours (i.e., were underemployed) in Q4 2020. This decreased to 76% in Q4 2021, 72% in Q4 2022, and 61% in Q4 2023, but rebounded to 68% by Q4 2024 (Figure 3).

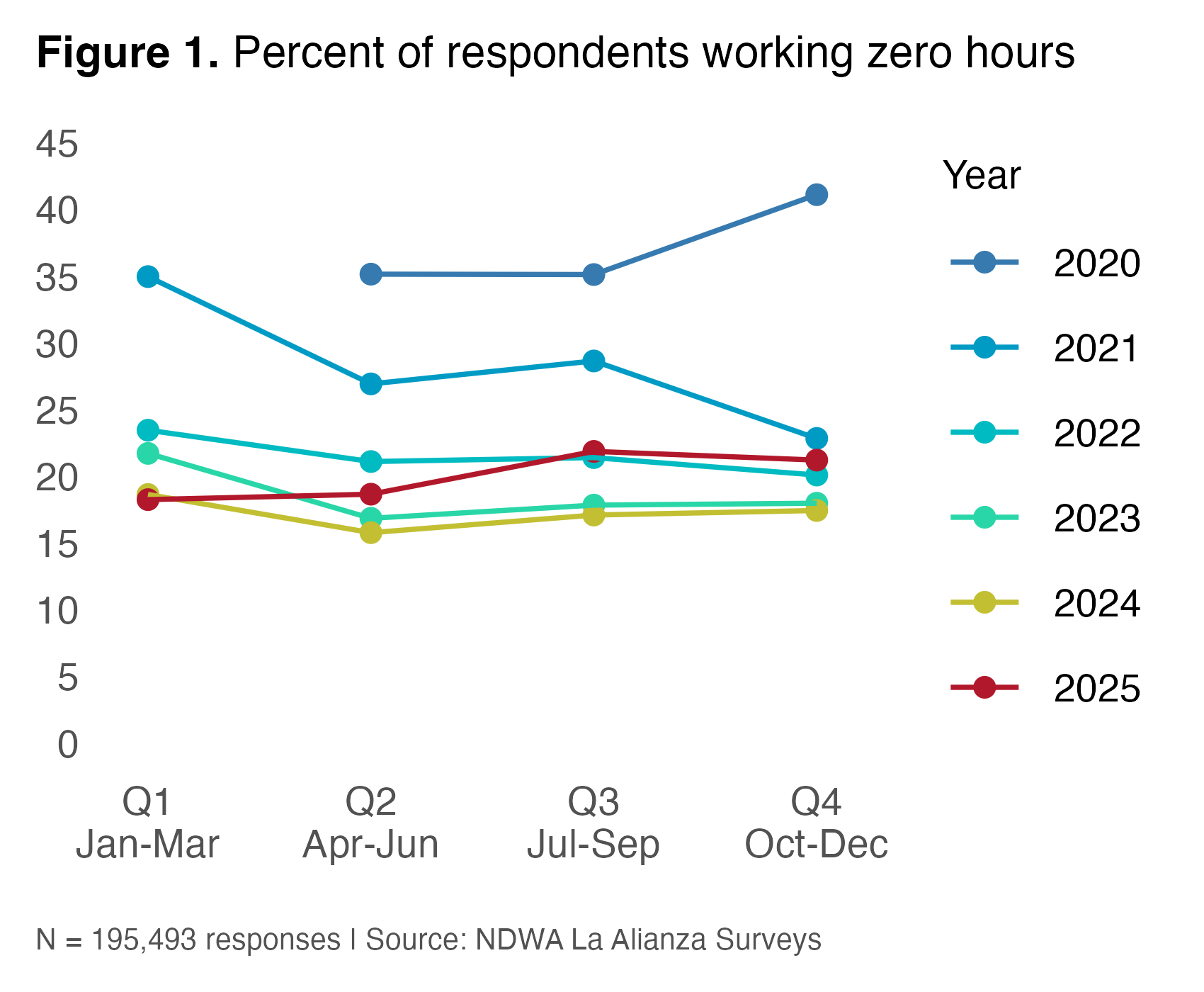

Initial abatement and resurgent vulnerability in economic precarity. Although the share of domestic worker respondents who could not pay their rent or mortgage on time in the last 30 days fell sharply from 2020 (65% in Q4) to 2021 (44% in Q4), with some continued progress in 2022 (41% in Q4), subsequent years of data indicated a concerning reversal in this pattern (Figure 2). Housing insecurity rose again over both 2023 (49% in Q4) and 2024 (56% in Q4), at times nearly matching 2020 levels.

Taken together, by the end of 2024, employment conditions suggested cautious optimism about the possibility of continued progress in 2025, whereas data on economic circumstances suggested workers were already struggling and vulnerable to new threats.

Changing employment and economic conditions during 2025

At the start of 2025, domestic worker respondents’ employment and economic conditions largely mirrored those at the end of 2024. Their situation worsened over the course of 2025, with a sharp deterioration in Q3—especially for economic conditions—that largely persisted in Q4.

A tenuous recovery in employment conditions unravelled. After decreasing for years, the percent of respondents working zero hours rose from 18% in Q1, to 19% in Q2, 22% in Q3, and 21% in Q4 2025, putting Q3 and Q4 levels on par with those from 2022 (Figure 1).

The percent of underemployed respondents was 64% in Q1, 65% in Q2, 74% in Q3, and 72% in Q4, also putting Q3-Q4 2025 underemployment on par with 2022 levels (Figure 3). The share of domestic workers earning $14 or less also ticked upwards in Q3 and persisted into Q4 2025 (Q1: 45%, Q2: 46%, Q3: 51%, Q4: 50%).

A vulnerable economic situation deteriorated sharply in Q3 and persisted in Q4. Housing insecurity—which had already risen well above 2021 levels by the last half of 2024—rose again from 52% in Q1 2025 to an all-time high in Q3 2025, with 62% of respondents unable to pay their rent or mortgage on time in the last 30 days (Figure 2). Survey platform interruptions led to non-collection of monthly economic data in October 2025. Data from the rest of Q4 indicated 58% of respondents in November and December could not pay rent or mortgage on time.

Food insecurity (i.e., food was sometimes or regularly scarce in their household in the last 7 days) has rarely dipped below 80% since 2022. In 2025, the share of respondents experiencing food insecurity was 82% in Q1, 81% in Q2, and 88% in both Q3 and November/December of Q4.

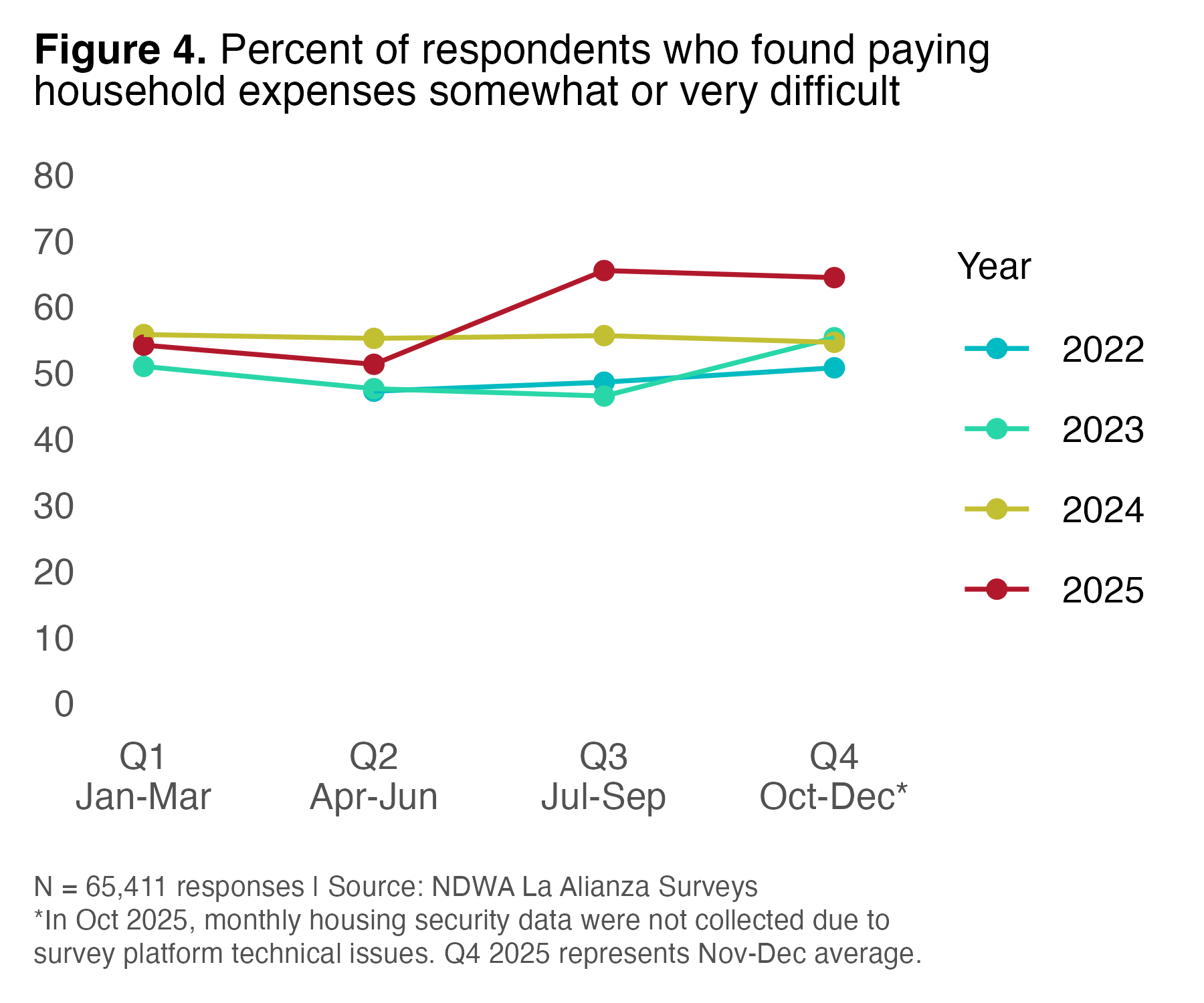

Finally, the share of respondents who found it somewhat or very difficult to pay regular household expenses in the last 7 days broke sharply with prior patterns in the second half of 2025—going from 54% in Q1 and 51% in Q2 to 65% in Q3 and 64% in November and December of Q4 (Figure 4). This represents the highest level of overall economic insecurity reported by respondents since NDWA began measuring it in March 2022.

Mental health and working conditions

Data from two newer survey modules showed that workers’ mental health suffered a severe blow towards the end of 2025 as workplace conditions and worker power deteriorated.

Poor psychological well-being spiked from 50% in Q3 to 66% in Q4 2025. Psychological well-being is measured quarterly and scored using a threshold from the World Health Organization. Two-thirds (66%) of the domestic workers who responded to this survey module in October reported poor psychological well-being. This represents a substantial spike from prior quarters of 2025, as well as from when this module was piloted in Q2 2024 (43% had poor psychological well-being).

Worsening power dynamics in Q4 2025. The share of domestic worker respondents who reported sometimes or regularly being treated disrespectfully at work increased steadily in 2025 from 32% in Q1 to 34% in Q2 and 38% by Q3 and Q4.

The share who felt very comfortable asking their employer for a sick day dropped to just 9% in Q4 as more workers became somewhat uncomfortable asking for a sick day (Figure 6).

In addition to these concerning shifts in measures related to power imbalances and employer behavior, other job quality metrics also deteriorated. For example, among the minority of respondents with a written contract for at least one of their domestic work jobs, the percent whose contract included paid days off dropped from 38% in Q2-Q3 to 23% in Q4 2025.

Understanding the drivers of change: Worker voices and supporting survey data

La Alianza surveys track employment and working conditions over time, but understanding why conditions changed requires hearing directly from workers. This section presents first-hand accounts from peer interviews and group discussions conducted during Spring-Fall 2025 as part of a NDWA Worker Council Peer Research Project (Text Box 1), alongside supporting survey findings.

The interconnected nature of 2025’s crises emerges clearly from these interviews: what began as growing fear and uncertainty in the Spring evolved into widespread job loss and economic hardship by Fall.

Text Box 1. NDWA Worker Council Peer Research Project

For the first time, this La Alianza Domestic Worker Survey report highlights first-hand accounts from domestic workers collected as part of the NDWA Worker Council Peer Research Project.

NDWA Worker Councils—the Nanny Council, Home Care Workers Council, and Housecleaners Council—are important national leadership bodies made up of experienced domestic worker leaders who are members of NDWA, NDWA Chapters, or Affiliate Organizations.

In May 2025, as part of a larger worker-led research initiative, Worker Council members co-created research priorities and tools to gather first-hand stories from fellow domestic workers in their respective sectors. From May-June 2025, 26 council members conducted semi-structured interviews with 75+ workers across 15 states about how and why working conditions were changing in 2025. In October-November 2025, 27 worker council members interviewed 60+ workers across 12 states about changing conditions and their impacts. Council members shared the findings from their interviews and reviewed Q3 La Alianza survey findings, reflecting collectively on the interconnected causes and compounding crisis facing their communities.

Importantly, we do not know whether Worker Council interviewees also participated in La Alianza surveys. The identifying information needed to create these linkages was not collected to protect domestic worker privacy and confidentiality.

Pervasive fear began disrupting work and daily life in Spring 2025. In the Spring, worker council interviewees mentioned “fear” over 60 times—across all domestic work sectors and all over the country. Fears related to immigration enforcement were the most prominent, but not the only ones workers mentioned (e.g., Medicaid cuts impacting clients with disabilities and worker families). And although undocumented workers and workers with undocumented family members bore the brunt of these fears, even resident and citizen workers were not safe. As a nanny from Chicago explained:

“Even though many have papers, they don’t feel safe. Many were impacted even though they are residents or citizens. The fear of going out is the same for everyone. If you are Latino, there is fear.”

These fears led to more difficulty finding and keeping work as early as Spring 2025. As a house cleaner from Washington state described, some workers stopped seeking jobs the way they used to (e.g., flyers, online advertisements, door-knocking):

“They aren’t looking for jobs the way they used to—going out knocking doors. They aren’t taking every employment opportunity that comes up. Before they would take whatever came through, not anymore. There is fear of leaving the house.”

Getting to and from work also became particularly fraught, with workers avoiding public transit or requesting rides to feel safer, even when it meant income loss. A nanny in Texas shared that among the workers she spoke to some “are looking for new job opportunities where they do not have to commute because they are scared of a random traffic stop.” Another nanny interviewed in California lives in Oakland and works in another city, which means:

“She has to take BART, then a bus, and walk 20 minutes to get to the family's house where she takes care of children...She says, ‘The pay is low, they give me few hours, and on top of that, I'm exposing myself to everything that's going on.’ She decided to leave the job and is looking for new work."

In addition to these difficulties finding and keeping work related to fears of immigration enforcement, some workers also reported that their employers had reduced their hours, conducted excessive interviews, or fired them out of their fears of immigration enforcement.

A cascading economic crisis crystallized by Fall 2025. By the Fall, domestic workers’ fears had crystallized into an economic crisis. Workers faced impossible choices as they navigated immigration enforcement, lost work and income, decreased demand and depressed wages for their services, rising costs of living, and intense difficulty making ends meet.

Multiple workers described how the threat of immigration enforcement translated into lost work and income. Some whose husbands were detained by immigration officers were forced to lose work hours as they sought help. Others left their jobs pre-emptively, as a nanny from Chicago described:

“In many cases, both parents are undocumented. So domestic workers have had to leave their jobs, either because their work is far away and they have to care for their children, and one of the two needs to stay protected. So they’ve had to make a choice about who leaves their job.”

Meanwhile, some people kept working despite the continued threat of immigration enforcement out of economic necessity, as the same nanny went on to explain: “Many decide to keep working and continue to put their stability at risk because life goes on here, and they say, ‘we have to eat, we have no choice.’”

Those who continued working faced diminished prospects on the domestic labor market for multiple reasons. Employers faced economic problems of their own, leading some to fire workers and others to cut back on housecleaning services as a “luxury” expense they could no longer afford. Domestic workers also described a recent influx of workers from other industries (e.g., retail, restaurants) into domestic work. This drove down industry standards, as a house cleaner in Washington explained: "So now they're gardeners, house cleaners, nannies for a low salary because they don't know their rights. And we're also losing work because they're offering these services.”

Workers also attested to the fact that this cascading crisis was giving employers leverage to worsen working conditions. They described rising wage theft, increased responsibilities without increased pay, and acute fears of employer retaliation. A home care worker in Massachusetts captured the interconnectedness of deteriorating economic conditions and these types of exploitation:

"Everything stems from politics, because right now, migration, the tariffs—it's affecting the country's economy. So, business closures are affecting us....It has raised the prices of food items and everything else. Employers are taking advantage of jobs because they know we need the work. And there are no jobs. So, those who have jobs exploit us. It's a chain, everything goes...Everything leads from one thing to another."

Finally, worker testimony shed light on how these Spring-Fall 2025 employment challenges translated into acute difficulties paying for basic needs so quickly. Before 2025, domestic work wages were already not enough or barely enough to survive on. Anyone who had previously had built up some savings saw them depleted during the pandemic. And, unlike during the pandemic, workers now described avoiding food banks or other forms of public assistance due to fear of immigration enforcement.

Survey data confirmed safety as a significant, if fluctuating, concern for workers seeking more hours. Among workers who were underemployed in the last four months of 2025, inability to find clients remained the primary barrier to working more hours throughout the year (ranging from 57-64%). However, when NDWA added "I don't feel safe" as a response option in September 2025, it immediately emerged as a significant secondary barrier.

Safety concerns peaked in September and October, when 22% and 23% of underemployed workers, respectively, selected this as their primary reason for not working more hours—coinciding with heightened immigration enforcement operations in the Washington D.C. area and Illinois. By November and December, this dropped to 9% and 13%, though this decline does not necessarily indicate reduced risk. Workers who stopped working entirely due to safety fears would not appear in the "underemployed" category this question targets. As testimonies suggest, many workers simply had no economic choice but to return to work despite continued dangers.

Of note, we sent two special surveys to domestic workers in Washington D.C., Maryland, and Virginia (the DMV area) on September 12, 2025 and in Illinois on October 10, 2025 amidst ongoing immigration enforcement operations and National Guard deployments to those areas. We asked about workers’ experiences finding and retaining work recently. Among those who were asked why it was more difficult to find or keep work recently, 28 of the 50 respondents to this question (56%) in the DMV area and 17 of the 24 respondents in Illinois (68%) said it was because they didn’t feel safe. The number of respondents to these special surveys was—as expected—much smaller (80 total respondents in the DMV area; 54 in Illinois) and we asked about safety in a different sequence than typical in La Alianza surveys.

Why this matters

Data from 2025 documents a significant, systemic reversal of post-pandemic recovery in domestic workers’ conditions. After years of gradual, if uneven, improvement in employment, conditions deteriorated sharply in Q3-Q4 2025—returning to 2022 levels. Even more alarmingly, multiple measures of economic insecurity reached the highest levels recorded since tracking began in 2020, surpassing even pandemic-era peaks. Worker testimony revealed cascading harms between fears of immigration enforcement, economic precarity, job loss, and increased employer exploitation. Taken together, these findings raise deep concerns about what comes next for domestic workers and all who rely on them in 2026.

Despite growing resistance and shifting public opinion, attacks on immigrants and workers by the second Trump administration show no signs of relenting. The cascade of harms to domestic workers documented here is likely to continue and deepen. Workers' deteriorating economic position gives employers increased leverage to impose worse conditions—lower wages, longer hours, no contracts, no paid time off. The influx of workers from other industries into domestic work, as evidenced by nationwide data on the 2025 labor force and documented in worker testimonies, further floods the market and drives down standards. The erosion of worker power visible at the end of 2025 may be just the beginning.

This matters beyond domestic workers themselves. Although no official recession occurred in 2025, Black women workers across the US—sometimes framed as a “canary in the coal mine” for the broader economy—experienced rising and recession-level unemployment rates. Other industries that rely heavily on the labor of immigrants such as construction and agriculture also saw stark employment losses and are expected to suffer more in the coming years. Disruptions to domestic work also warns of broader economic danger, considering how individuals, families, and institutions depend on domestic workers’ care in ways that make this workforce uniquely central to daily life.

As captured by the house cleaner whose words inspired the title of this report, domestic workers “keep fighting, but these are terrible times.” The path forward requires recognizing both the severity of this crisis and all that is needed to resist it. Domestic workers will continue organizing, caring for one another, and fighting for dignity and fair treatment, with support from NDWA and affiliate organizations. As a research team, our reports will continue documenting domestic workers’ conditions and voices through 2026 to inform efforts to address this crisis.

To learn more about NDWA’s La Alianza survey, see our methodology report.